What Can the Social Sector Learn from Tech Startups?

Tech startups have a tried and true playbook for growing a user base and delivering value for customers—can the social sector use it?

One of the ideas we've been exploring through the Social Impact Fellowship is whether there are ideas and practices in the tech sector that might be valuable for social entrepreneurs. As it turns out, the tech industry and the social sector are often thinking along the same lines, but they use different tools and mental models.

Here, we unpack some industry practices that might be useful for people working on poverty reduction. In a future post, we will explore a few ideas from the social sector that could help tech entrepreneurs.

1: Metrics

Startups tend to be obsessed with metrics: the signals quantifying how users interact with your product, whether they find value in the problem being solved, and whether you are approaching “product-market fit”.

After decades of investing by firms like a16z and YC, there are now generally agreed metrics that most tech founders focus on. Prime among these are Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) and Life-Time Value (LTV).

Customer Acquisition Cost

CAC comprises the marketing, media, sales, and even onboarding efforts required to bring new users to your product. It is distinct from the costs of producing a service or operating a business. This is intentional: conventionally, customer acquisition is expensive – but as you get better at targeting your product to the people who value it most (i.e., those who will pay), your acquisition costs can decline. You also might find new partners or channels for marketing, which reduces CAC further. Tracking these expenses separately allows for experimentation and iterative improvement in the process of user acquisition.

The social sector varies widely in its approach to cost metrics. While accounting and monitoring are well-established practices at most mature non-profit organizations, there are few widely agreed metrics – especially as it relates to costs. A few agencies, like the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), have established guidelines for estimating the economic rate of return for social investments. But most non-profits simply budget and track costs on the basis of individual projects, since this is the way donors fund. They rarely experiment with ways to reduce CAC over time.

What does CAC look like for a non-profit? At the start of a new project, an organization might use existing data to map potential users across a targeted geography. More research-oriented NGOs, like BRAC, will run a light-touch census of households in a new area when deciding whether to open a new branch. Organizations might also collect some demographic data to guide the targeting of their services (to ensure that the neediest users are supplied first).

But these expenses are rarely tracked separately in the form of a CAC. Relatively little attention is paid to improving the process of acquiring and onboarding users. What if NGOs routinely measured CAC and used this metric to find the most efficient (and respectful) ways of reaching clients? To do this, they would need to know whether they are reaching the users who could benefit most. Which brings us to our second concept… Life-time Value.

Life-Time Value

LTV is a startup metric that captures the total value of a customer’s purchases over the lifetime of their consumption of a product. This allows companies to forecast the likely revenue generated by a given type of customer. The ratio of LTV to CAC can inform your targeting, help you calibrate spend on user acquisition, and inform your growth strategy.

In the social sector, the value we care about is social impact. We're not in the business of generating revenue. We want to create value for users, but we don't measure it in profits. Instead, we might care about additional years of schooling attained, increased household income, improved child nutrition, or reduced suffering.

So suppose we reframe LTV as the expected lifetime value that a user will receive from our product. Here, we are shifting the accrual of value from the firm to the individual. This might help us identify which users to target. The more a person will benefit from the extra schooling, income, or nutrition generated by your product, the higher the LTV.

We can further refine our definition of LTV by applying a discount rate on benefits accrued in the future, so that benefits received early on are valued higher than benefits delivered in later years. We can also incorporate the principle of marginal utility, a favorite among effective altruists. According to the law of diminishing marginal utility, an extra dollar matters relatively little to someone who makes more than $75,000 per year. The value of that dollar is greatest for the poorest people. So perhaps we calibrate LTV according to a user’s baseline consumption.

With our newly defined LTV, we can begin to optimize marketing, user onboarding, and other user interactions. The ratio of LTV to CAC helps us evaluate whether a given strategy is delivering adequate value for the expected costs.

Of course estimating LTV requires a lot of assumptions. There isn’t much data on the long-term impacts of most social services. Deworming is a notable exception: researchers have estimated the 20-year impacts of school-based deworming, finding that adults who were treated as kids have 14% higher household expenditure – and 13% higher hourly earnings – compared to controls. While you might not nail your expected LTV, there is enough academic research (from orgs like J-PAL, IPA, and CEGA) that you can probably make an informed guess.

How is all of this different from an economic rate of return, or a cost-benefit analysis (both of which are used in the social sector)? For one, LTV is a dynamic figure, and it is expected to shift based on management decisions about a product or service. In comparison, cost-effectiveness is usually estimated at a single point in time, either at the start or end of a project. Here’s an example, from the education sector:

In the social sector, we rarely explore whether the costs (and benefits) of the program might be dynamic over time, or based on changes in implementation.

A second difference is that LTV varies by user class. Startup founders assume that their users are heterogeneous, and generate LTV estimates for each segment of their user base. Some users may quickly adopt a product but fail to use it reliably over time. Other users may take time (and marketing effort) to convert, but once they’re a paying customer, they stay engaged. Sadly, the social sector has lagged in recognizing the importance of heterogeneity when testing out new products or services (in most cases because sample sizes are too small).

2: Funnel Analysis

Once you have the right users onboarded, you need to retain them – which requires ongoing engagement and generation of value. If your product stops offering value, your customers will drop out of the funnel.

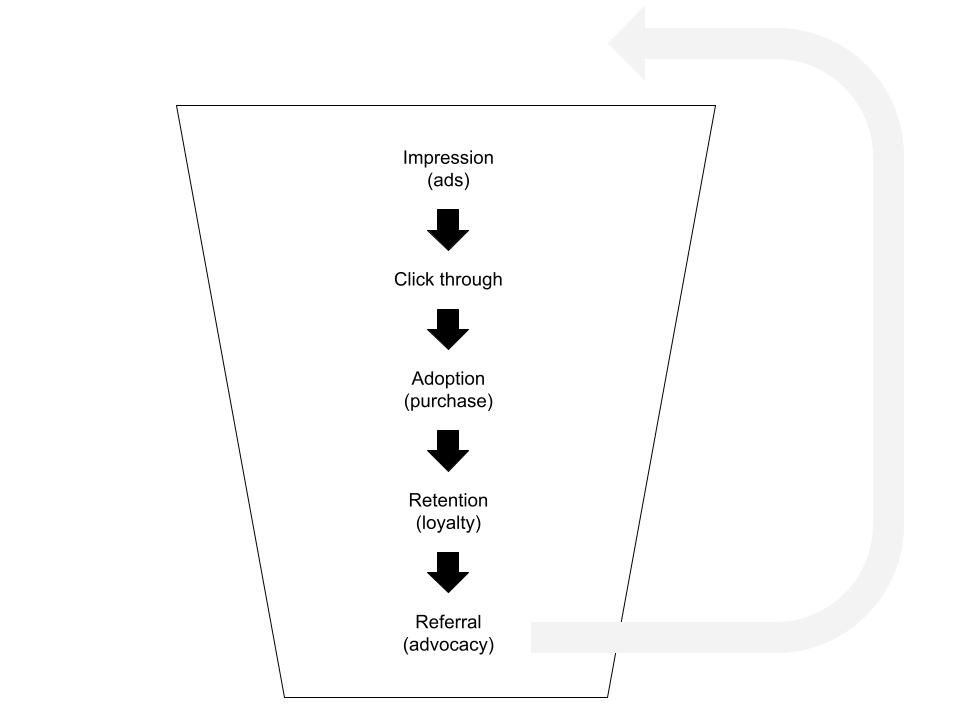

For online services, the typical user journey looks something like this:

In the context of a social venture, the journey might start with a user’s exposure to an organization’s frontline staff, leading to the adoption of a new practice (or a change in behavior). Ultimately, this generates some long-term impact.

A key insight is that tech companies, especially in e-commerce, hyper-optimize each of their core user flows – from user onboarding to purchase experience – through funnel analysis. Companies record data at every stage in the funnel to understand exactly where users drop-off. At which point do customers stop purchasing or using a product, and why are they no longer finding value?

Product developers then try to remove all possible sources of friction (e.g. eliminating distracting user interface elements, minimizing the required number of clicks to complete an action, adding fields that autocomplete, etc). Even with huge investments in this area, most companies still convert fewer than one in 10 users who visit a site. Because of that, even small improvements in conversion rates make a huge difference to a start-up’s bottom line.

Social entrepreneurs might consider a similarly rigorous approach to their intervention’s most important user flows. With some non-profit services, getting the user onboarded is the hardest part. So we might experiment with different strategies to reduce the effort required: we might cut back on the amount of upfront information requested, or allow users to authenticate with existing identity services (like Aadhaar in India). We might even let people try out the intervention before committing.

If the steepest challenge is adoption of a new practice, we can similarly make changes to the model, and track user retention (or other funnel metrics) across different variants of the service. This brings us to our final concept…

3: Rapid Experimentation

Much of the success of the fastest growing companies is attributed to their fast pace of learning. This takes many shapes – from actively seeking customer feedback in public channels, to testing out early versions of products internally (dogfooding). But perhaps the primary way that product-focused tech companies rapidly improve their offerings is by running A/B tests, or “experiments”. For those more familiar with academia, A/B testing is simply another form of a randomized controlled trial.

The power of A/B testing is that it allows for companies to make continuous changes in their offering, all while tracking user metrics – everything from CAC and LTV, to the funnel metrics (like user engagement, retention, and referral). The changes with the biggest impact on revenue and profits can then be deployed at scale.

While large user bases and short feedback loops make A/B testing much easier for consumer-facing tech companies, social entrepreneurs can also iterate and improve on their interventions. Youth Impact is an example of a non-profit organization that runs A/B tests in the “real world”, by randomizing high school students to different classrooms, and then delivering variants of their curriculum to see which works best. They run monthly experiments, resulting in continuous improvements in their impact on adolescent health and education.

One of the easiest takeaways is to adopt a culture of experimentation and continual learning and improvement. Even though Google Search is almost 25 years old, Google is still running hundreds of simultaneous tests to improve various facets of the product. More tactically, building the infrastructure to successfully run A/B tests has organizational benefits. For example, A/B testing helps you make your target metrics concrete – and it forces you to reliably measure them as you shift product design. Importantly, A/B testing also helps prevent various biases from unexpectedly creeping into organizational management decisions.

We’ve gone through a few industry practices here, but there may be others that are useful in the social sector. For example, tech companies often utilize influencer marketing to gain users in a new market. Influencers with large audiences might be willing to help social entrepreneurs with missions that align. Startups also evaluate the size of every new market they consider entering before starting to experiment; they call it the total addressable market, or TAM, and it’s an estimate of how many people might value a given product or service. Similarly, non-profit founders may want to tackle the problem spaces with the strongest “market” (or potential) for social impact. How many future users might benefit, and how significant is the benefit to them? Sometimes tying numbers to these ideas – even if they’re just rough estimates – can guide decision-making in valuable ways.

Temina Madon is a co-head of community at SPC, co-founder of the Agency Fund, and professional faculty at UC Berkeley. Piyush Poddar is an SPC-Agency Fund Social Impact fellow and social entrepreneur with six years of experience building products at both Google & Stripe.