Ashton Eaton: From Olympic Gold to Tech

Two-time Olympic gold medalist Ashton Eaton made an art out of breaking his own world records during his decorated decathlon career. He…

Two-time Olympic gold medalist Ashton Eaton made an art out of breaking his own world records during his decorated decathlon career. He started out at the University of Oregon, where he was a five-time NCAA champion and graduated with a degree in psychology in 2010. Soon after launching his professional career, Eaton set two world records in 2012 and, later that year, achieved his lifelong dream of winning Olympic gold at the London summer games. In 2016, he won his second Olympic gold medal in Rio de Janeiro, becoming the third athlete to win back-to-back golds in the decathlon.

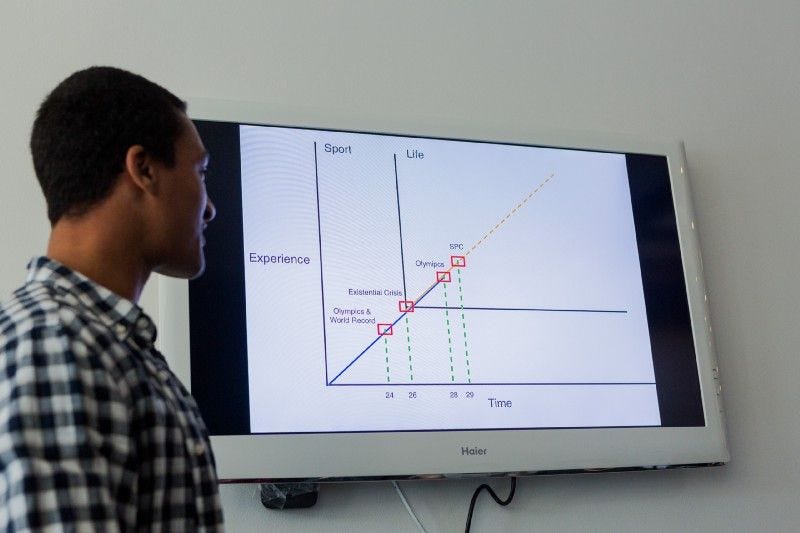

In early 2017, after months of reflection, Eaton announced his retirement from the sport. He and his wife, Olympic bronze medalist Brianne Theisen-Eaton, prepared to move to San Francisco, where they are now working on a new technology and wellness venture. In December, Eaton joined as a new member of South Park Commons and sat down with SPC founder Ruchi Sanghvi to talk about winning, the mental and physical routines that led him to victory, and how he plans to keep beating his own personal records, even off the track.

Great expectations can do great harm

For Eaton, winning Olympic gold was more about personal satisfaction than triumph. The year before his first Olympic Games, in 2011, he was the unquestioned favorite to win the World Championships. It was Eaton’s first year as a professional athlete, and his trial run for Worlds was the best score in the world by a large margin. But despite these expectations, Ashton came in second in the competition.

Eaton recalled standing on the podium to receive his silver medal as a uniquely motivating moment in his life: “I thought, this is amazing. Then, I looked up at the guy on the first-place podium and thought, but if this is amazing, I wonder what that feels like. I wanted to do everything I could to get there.” For Eaton, it was a massive turning point. “I know that if I had won that world championship, I would not have won the Olympics.”

Eaton never lost from then on out — freeing himself from expectation allowed him to focus on skill and personal fulfillment above anything else. “I’ve come to understand expectation versus reality. When I expected to win, my expectation made me do worse.”

“When I was younger, I used to look at the Olympians and try to understand how they were doing what they were doing. I practiced and trained with the curiosity of what it would take to get to that level.” Today, Ashton looks at founders and entrepreneurs who are positively contributing to the world with the same mentality. “I don’t know what I’m capable of,” he said, “but my mentality is the same as it was when I was a young athlete. I have no expectations, just wonder about what’s possible.”

Prepare for uncertainty, then embrace it

In An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth, Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield describes how his NASA training led him to embrace a “success-and-survival” philosophy that taught him to “prepare for the worst — and enjoy every moment of it.” Eaton adopted Hadfield’s strategy as a way of preparing himself for competition: “One of the things I used to do, the morning or night before the Olympics, was think of all the things that could go wrong, and feel what that would feel like,” he said. “I thought about false starting, strong headwinds, two fouls in the long jump, getting injured… it gave me more leniency on myself to be able to operate at a high level in uncertainty. Because at the end of the day you can only control the controllables.” When something would occasionally go wrong during a race, Eaton had already anticipated it — and was primed to move forward.

You don’t have to win everything to win it all

The decathlon is a unique event, made up of ten constituent parts: four runs, three jumps, and three throws. It’s nearly impossible to win every event, so winning the decathlon usually means losing, too. “My event is great, because you know you’re going to lose something,” Eaton said. “I’m never going to win all ten events.”

Eaton is fast and agile. To win overall, he maximized his strength in the high-scoring speed and jumping events, and minimized his losses in the throwing events. “Even though I lost in some parts of the event, I still always had the possibility of victory.” There’s a lot of awareness required to find what you’re the best at and accept that you don’t have to win everything to win it all. Eaton has applied this same approach elsewhere, maximizing his expertise and finding partners who have different skill sets or who can help identify his personal blind spots.

Use the valleys to develop mental resilience

“A couple of years after my first Olympic gold in London, I thought about quitting for the very first time in my life. A thought just came into my mind: you’re just running in circles, what are you doing? Why are you doing this?” In trying to understand the sudden desire to quit, Eaton realized that developing mental resilience is not unlike developing physical strength. “I snapped out of it, realizing that I was just getting in my head post-win. I began to understand that the way we get physically strong is to go the weight room and break down muscles, resisting against the weight. So I thought, it has to be similar mentally. All these doubts, pressure, fears, anxieties — that’s resistance, and the more you can lift up against it, that’s how you get stronger.” That mental resistance kept him on the track and led him to his second gold in Rio de Janeiro.

“In order to have a peak, you have a valley,” he said. “For a while, I hated peaks, because I knew there was going to be a drop afterwards. But now I anticipate and look forward to them, knowing they are an opportunity to build strength and resilience for whatever comes next in my life.”

Increase the good, decrease the bad, direct the questionable

Part of Eaton’s dilemma over quitting also stemmed from the fact that at 24, he had already accomplished his goal of a gold medal and did not immediately see the point of training to repeat his success. “It was the end of the line, there was nothing after,” he said. “I’m the type of a person who doesn’t like achieving an objective of equal value twice. So to keep going, I had to reframe things.”

Around that time, he picked up a book that helped him reconfigure his approach to life as a journey toward self-improvement rather than victory. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense led him to discover the writing of Nikola Tesla, the Serbian-American physicist and engineer for whom the unit of energy is named. In Tesla’s short work, The Problem of Increasing Human Energy, Eaton found inspiration: “Tesla showed me that the goal is progress. And in a way, progress is intangible,” he said. “It requires that you move forward, even if you accomplish what you set out to do”Re-framing his goal in terms of progress, rather than a gold medal, helped Eaton decide to compete in the next Olympic games. In his training, Eaton followed Tesla’s formula for progress: “increase the good, decrease the bad, direct the questionable.”

“I plan to apply Tesla’s writings to this next venture. The inputs are different than track, but the application of Tesla’s philosophy is the same. With a company, you have all these different people, moving in different directions. The progress of your company, or your task, is the sum total of all these directions. The more you can effectively direct them, the more progress you actually make toward your goal.”

Back to a beginner’s mind

When Eaton was starting out, he trained hard and long — hours of practice and repetition to master events that were then very new to him. The time spent practicing was enormous, but so was the pay off. “It was so satisfying to see how quickly I could learn and improve.”

Eaton’s practice routines shifted as he advanced in his career. “When you develop expertise, you make fewer attempts of higher quality in practice.” Injuries tend to happen when high-level athletes try to spend more time practicing at an unsustainably high level. As someone who’s motivated by progress and improvement, it was rare for Eaton to leave a practice session feeling completely satisfied: “By the time I became an Olympian, I probably left 90% of practices feeling completely frustrated,” he said. “When you’re at the top level, the advancements are rarer, and they are lesser in magnitude,” Eaton said. “That’s why my wife and I decided to retire — because although we were getting better, we were doing so slowly. And, the things we were getting better at were not improved by much.”

“When you do something new, the improvements are super vast. And even though that initial phase is difficult and requires a lot of time, you actually can feel yourself growing. “That feeling of growing, it’s like…yes.”

Since retiring and moving to San Francisco, Eaton has been feeling a lot of yes. The career change means that he’s a beginner again, so he can look forward to newer, faster advancements as he experiments with software and hardware technology and shaping his new health and wellness venture. “That’s why I’m here,” he said. “I’m motivated by that same feeling I had early on as an athlete. I’m actually looking forward to digging into the things that are most challenging, as facing them will likely determine my success later on.”

You can watch the full fireside chat with Ashton on YouTube.

Taking some time to figure out what to do next? Consider applying to SPC!